Researchers predict that steep declines in population in most countries will have negative effects on future generations. However, adapting to this trend is possible.

In 1970, a woman in Mexico could expect to have, on average, seven children. By 2014, this number had dropped to about two. Starting in 2023, it was only 1.6. This means that the population is not having enough children to sustain itself.

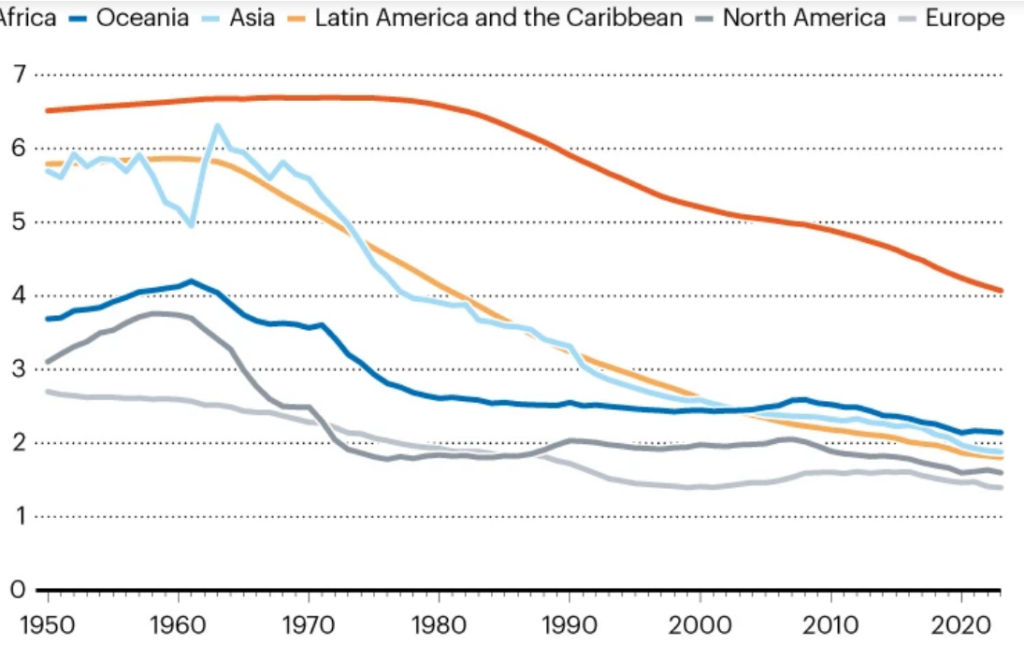

Mexico is not the only case: countries around the world are facing declining fertility rates. Exceptions are few. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington, Seattle, estimates that by 2050, over three-quarters of countries will be in a similar situation.

"There has been an absolutely incredible decline in fertility - much faster than anyone anticipated," says Jesús Fernández-Villaverde, an economist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. "And it's happening in many countries you wouldn't have guessed."

The numbers are clear. What is uncertain is how problematic this "population decline" will be globally and how nations should react, as stated in an article published by Nature.

In economies built around the prospect of constant population growth, concern is tied to future declines in innovation and productivity, as well as the fact that there are too few working-age citizens to support an increasing number of elderly individuals.

Researchers warn of chain effects, from weakened military power and reduced political influence for countries with low fertility rates to fewer investments in green technologies. Countries need to address the population decline and its impact now, says Austin Schumacher, a health indicators researcher at IHME.

"We're not having children. The human race is not perpetuating," says Barbara Katz Rothman, a sociologist at New York University.

Many countries have tried to take measures, and data suggest that some strategies are helpful - even if they are under political pressure. But for scientists familiar with the data, it's possible that not even the most effective efforts will bring about a complete reversal of fertility rates.

That's why many researchers recommend shifting the focus from reversal to resilience. They believe there are reasons for optimism. Even if countries can only slow down the decline, it should give them time to prepare for future demographic changes.

Ultimately, scientists say, low - but not too low - fertility rates could have some benefits.

What the data shows

In the mid-20th century, the global total fertility rate - generally defined as the average number of children a woman would have during her reproductive years - was five.

Population growth has slowed over the past 50 years, and the average total fertility rate is 2.2. In about half of countries, it has dropped below 2.1, the generally necessary threshold to maintain a constant population.

Small changes in these numbers can have strong effects. A birth rate of 1.7 could reduce a population to half its initial size a few generations earlier than a rate of 1.9, for example.

How fertility has declined

The case of South Korea deserves careful analysis. The fertility rate dropped from 4.5 in 1970 to 0.75 in 2024, and the population peaked at just under 52 million in 2020. This number is now decreasing at a pace expected to accelerate.

Demographers generally expect the global population to peak in the next 30 to 60 years and then contract. If this happens, it will be the first such decline since the Black Death in the 1300s.

According to the UN, China's population could have already peaked around 2022, at 1.4 billion. India's could do the same in the early 2060s, reaching 1.7 billion people. And, taking the most likely immigration scenario, the US Census Bureau predicts that the US population will peak in 2080, at around 370 million people.

Meanwhile, some of the sharpest short-term declines are anticipated in middle-income countries: Cuba is expected to lose over 15% of its population by 2050.

Sub-Saharan Africa is a notable exception. By 2100, over half of the world's children may be born there, despite the region having some of the lowest incomes in the world, the weakest healthcare systems, and the most fragile food and water supplies. Nigeria's fertility rate remains above four, and its population is projected to grow by another 76% by 2050, making it the third most populous country in the world.

However, fertility rate trends are hard to predict. Essential data is missing, and many models rely on the expectation that rates will rebound, as they have in the past.

What causes this decline?

The factors behind the fertility collapse are numerous. They range from expanded access to contraception and education to changing norms about relationships and child-rearing. The debate continues on which factors matter most and how they vary by region.

Some factors reflect positive societal changes. In the United States, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that fertility has declined in part due to fewer unplanned pregnancies and teen births.

Youth in wealthy countries also form fewer partnerships and have fewer sexual relationships. Alice Evans, a sociologist at King's College London, has suggested that online entertainment surpasses real-world interactions and erodes social trust.

And as women worldwide gain education and career opportunities, many have become more selective.

Many young people also desire a deeper education to secure jobs that could be stressful and unstable. Therefore, even couples may delay having a child or face difficulties in conceiving due to being older.

Rising costs create additional pressures. A UN survey of over 14,000 people in 14 countries found that 39% cited financial constraints as a reason for not having children. In US cities, births have plummeted where home prices have risen most rapidly.

Other contributing factors include declining sperm counts, possibly due to environmental factors. Many potential parents also have growing anxiety about political and environmental instability, as highlighted in the UN survey.

It's not clear which of these numerous factors are most important in each country. But ultimately, low fertility rates "reflect flawed systems and institutions that prevent people from having the number of children they desire," says Stuart Gietel-Basten, a sociologist at the University of Science and Technology in Hong Kong. "This is the real crisis."

Countering the decline

The consequences will manifest differently worldwide. Middle-income countries like Cuba, Colombia, and Turkey could be the most affected, with declining fertility exacerbated by emigration to wealthier nations.

The urban-rural divide will also deepen. As young people leave small towns, infrastructure like schools, supermarkets, and hospitals closes, prompting more people to move. Often, it's the elderly who remain.

Globally, aging is the primary issue of population decline. In countries with declining fertility rates, the proportion of people aged 65 and over is expected to nearly double, from 17% to 31% in the next 25 years.

As life expectancy increases, the demand for physical and fiscal support rises, but there's a gap in supply. For most countries hoping to halt declining fertility, there are tools. These include financial incentives, such as US President Donald Trump's proposal to give each newborn $1,000 in an investment fund.

Data shows that birth bonuses yield modest results in terms of fertility. Australia introduced a bonus of $3,000 in 2004, which was later raised to $5,000. Although the policy led to 7% more births in the short term, it's unclear if families had more children overall or simply chose to have them earlier.

Among more effective approaches, they say, are generous parental leave and subsidies for childcare and housing. Nordic countries have been pioneers in such investments, including paternity leave. These nations have seen slower declines in fertility than in other parts of Europe - though declines persist.